Lab3: Time-sharing Multi-tasking

In lab2, we implemented a Batch-Processing OS, allowing users to submit a bunch of programs at once then just wait for the result(s). Besides, we have made some basic security checks to prevent memory fault(or attack) in user’s programs influencing the other ones or OS. Despite the large labor-saving, it is still a far cry from a modern OS.

Think about how the OS behaves nowadays: Multi-tasking(you feel like doing many works at the same time), Real-time interaction(whenever click or press a key you get responses instantly), Memory Management, I/O Devices Management, and Networking utilities. It is those features, supported by complicated underlay mechanisms, that let us operate computers in a satisfying and efficient way. And in this lab, we are going to address the Multi-tasking problem, which takes an essential step towards our modern OS target.

The basic idea of multi-tasking on a single CPU is very simple: we run each task for a small piece of time, then switch to the next task and repeat this procedure. If we switch fast enough then it looks like we are running many programs at the same time.

The cruxes:

- How do we allocate memory of the programs? We need to preserve the task context (registers, stack, etc) in memory so that when we switch back and everything goes fine as before.

- How to switch between tasks? The OS code cannot run when the user’s programs occupy the CPU, so we need to seize this power from the user’s programs, without destruction to them.

- How do we schedule those tasks? What is the proper time interval to perform task switching? How do decide which one should run next?

In the following parts, we will discuss these problems, one by one.

0x00 Multiprogramming in Memory

Multi-program placement

As in Chapter 2, all application executables in ELF format are converted into binary images by dropping all ELF header and symbols with the objcopy utility, and then linking the application directly to the kernel data segment at compile time by embedding the link_user.S file in the OS kernel in the same format. The difference is that we have adapted the relevant modules: while in Chapter 2 the application loading and execution progress control are given to the batch submodule, in Chapter 3 we separate the application loading part of the functionality in the loader submodule, and the application execution and switching functions are given to the task submodule.

Note that we need to adjust the starting address BASE_ADDRESS in the linker script linker.ld used by each application to be built, which is the starting address of the application loaded into memory by the kernel. This means that the application knows that it will be loaded to a certain address, and the kernel does load the application to the address it specifies. This is a sort of agreement between the application and the kernel in a sense. The reason for this stringent condition is that the current operating system kernel is still weak and does not provide enough support for application generality (e.g., it does not support loading applications to arbitrary addresses in memory), which further leads to a lack of ease and generality in application programming (applications need to specify their own memory addresses). In fact, the current way of addressing applications is based on absolute locations and is not location independent, and the kernel does not provide a corresponding address relocation mechanism.

Since each application is loaded into a different location, the BASE_ADDRESS in their linker script linker.ld is different. In fact, instead of building the application’s linker script directly with cargo build, we wrote a script customization tool, build.py, to customize the linker script for each application:

# user/build.py

import os

base_address = 0x80400000

step = 0x20000

linker = 'src/linker.ld'

app_id = 0

apps = os.listdir('src/bin')

apps.sort()

for app in apps:

app = app[:app.find('.')]

lines = []

lines_before = []

with open(linker, 'r') as f:

for line in f.readlines():

lines_before.append(line)

line = line.replace(hex(base_address), hex(base_address+step*app_id))

lines.append(line)

with open(linker, 'w+') as f:

f.writelines(lines)

os.system('cargo build --bin %s --release' % app)

print('[build.py] application %s start with address %s' %(app, hex(base_address+step*app_id)))

with open(linker, 'w+') as f:

f.writelines(lines_before)

app_id = app_id + 1

Application loader

The way applications are loaded is also different from the one in the previous chapter. The loading method explained in the previous chapter is to have all applications share the same fixed physical address for loading. For this reason, only one application can reside in memory at a time, and the OS batch submodule loads a new application to replace it when it finishes running or exits with an error. In this chapter, all applications are loaded into memory at the time of kernel initialization. To avoid overwriting, they naturally need to be loaded to different physical addresses. This is done by calling the load_apps function of the loader submodule:

// os/src/loader.rs

pub fn load_apps() {

extern "C" { fn _num_app(); }

let num_app_ptr = _num_app as usize as *const usize;

let num_app = get_num_app();

let app_start = unsafe {

core::slice::from_raw_parts(num_app_ptr.add(1), num_app + 1)

};

// clear i-cache first

unsafe { asm!("fence.i" :::: "volatile"); }

// load apps

for i in 0..num_app {

let base_i = get_base_i(i);

// clear region

(base_i..base_i + APP_SIZE_LIMIT).for_each(|addr| unsafe {

(addr as *mut u8).write_volatile(0)

});

// load app from data section to memory

let src = unsafe {

core::slice::from_raw_parts(

app_start[i] as *const u8,

app_start[i + 1] - app_start[i]

)

};

let dst = unsafe {

core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(base_i as *mut u8, src.len())

};

dst.copy_from_slice(src);

}

}

// os/src/loader.rs

fn get_base_i(app_id: usize) -> usize {

APP_BASE_ADDRESS + app_id * APP_SIZE_LIMIT

}

Application Excution

When the initial placement of a multi-pass application is complete, or when an application finishes running or errors out, we want to call the run_next_app function to switch to the next application. At this point the CPU is running in the S privilege of the operating system, and the operating system wants to be able to switch to the U privilege to run the application. This process is similar to the one described in the section on executing applications in the previous chapter. The relative difference is that the operating system knows where in memory each application is preloaded, which requires setting the different Trap contexts returned by the application (the Trap contexts hold the contents of the epc registers where the starting address of the application is placed):

- Jump to the entry point of application $i$: $entry_{i}$

- Switch the stack to user stack

stack_{i}

0x01 Task Switch

The Concept of Task

Up to this point, we will refer to one execution of the application (which is also a control flow) as a task, and the execution slice or idle slice on a time slice of the application execution as a ” computational task slice” or ” idle task slice”. However, once all task slices of an application are completed, a task of the application is completed. Switching from a task in one application to a task in another application is called task switching. To ensure that the switched task continues correctly, the operating system needs to support “pausing” and “resuming” the execution of the task.

Again, we see the familiar “pause – resume” combination. Once a control flow needs to support “suspend-continue”, it needs to provide a mechanism for switching the control flow, and it needs to ensure that the program execution continues to execute correctly before the control flow is switched out and after it is switched back in. This requires that the state of program execution (also called the context), i.e., the resources that change synchronously during execution (e.g., registers, stacks, etc.), remains unchanged or changes within its expectation. Not all resources need to be saved, in fact only those that are still useful for the correct execution of the program and are at risk of being overwritten when it is switched out are worth saving. These resources that need to be saved and restored are called Task Contexts.

Design and Implementation of Task Switching

The task switching described in this section is another type of abnormal control flow in addition to the Trap control flow switching mentioned in Chapter 2, both describing switching between two control flows, which, if compared with Trap switching, has the following similarities and differences.

- Unlike Trap switching, it does not involve privilege level switching.

- Unlike Trap switching, it is partly done with the help of the compiler.

- As with Trap switching, it is transparent to the application.

In fact, a task switch is a switch between Trap control flows from two different applications in the kernel. When an application traps into the S-mode OS kernel for further processing (i.e., it enters the OS’s Trap control flow), its Trap control flow can call a special __switch function. This function is ostensibly a normal function call: after the return of the __switch, execution continues from the point where the function was called. But there is a complex control flow switching process hidden in between. Specifically, after the call to __switch and until it returns, the original Trap control flow A is first suspended and switched out, and the CPU runs another Trap control flow B applied in the kernel. Then, at some appropriate time, the original Trap A switches back from one of the Trap Cs (most likely not the B it switched to) to continue execution and eventually return. However, from an implementation point of view, the core difference between the __switch function and a normal function is simply that it switches stacks.

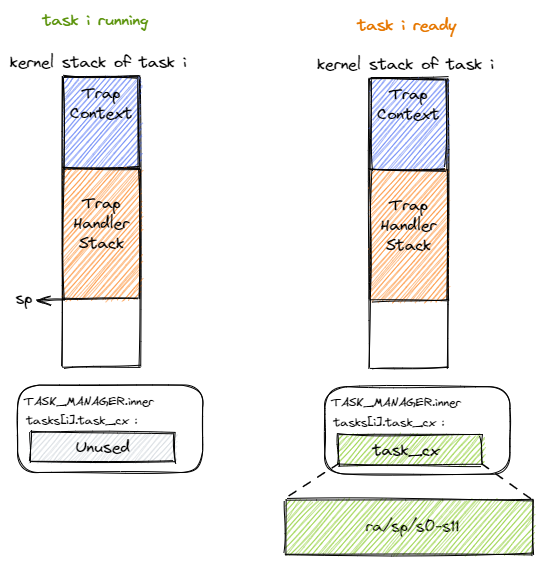

As the Trap control flow prepares to call the __switch function to bring the task from the running state to the suspended state, let’s examine the situation on its kernel stack. As shown on the left side of the figure above, before the __switch function is called, the kernel stack contains, from the bottom to the top of the stack, the Trap context, which holds the execution state of the application, and the call stack information left by the kernel during the processing of the Trap. Since we have to resume execution later, we have to save certain registers of the CPU’s current state, which we call Task Context. We will describe which registers to include in this later. As for where the context is stored, in the next section we will introduce the task manager TaskManager, where you can find an array of tasks, each of which is a TaskControlBlock, which is responsible for storing the state of a task, and the TaskContext is stored in the TaskControlBlock. At kernel runtime we initialize a global instance of TaskManager: TASK_MANAGER, so all task contexts are actually stored in TASK_MANAGER, which is placed in the kernel’s global data .data segment from a memory layout perspective. When we finish saving the task contexts, they are transformed into the state on the right side of the figure below. When we switch back to this task from another task, the CPU will read the same location and recover the task context from it.

For the Trap control flow of the currently executing task, we use a variable named current_task_cx_ptr to hold the address of the current task context and a variable named next_task_cx_ptr to hold the address of the context of the next task to be executed.

The overall flow of __switch from the point of view of the contents on the stack:

The Trap control flow needs to know exactly which Trap control flow it is about to switch to before calling __switch, so __switch has two arguments, the first representing itself and the second representing the Trap control flow it is about to switch to. Here we use the current_task_cx_ptr and next_task_cx_ptr mentioned above as proxies. In the above figure we assume that a __switch call is going to switch from Trap control flow A to B. There are four phases, and in each phase we give the contents of the A and B kernel stacks.

- Phase [1]: before the

__switchcall from Trap control flow A, the only information on the kernel stack of A is the Trap context and the call stack of the Trap handler, while B is previously switched out. - Phase [2]: A keeps a snapshot of the CPU’s current registers in the A task context space inside.

- Phase [3]: This step is extremely critical, reading the B task context pointed to by

next_task_cx_ptrand restoring theraregisters,s0~s11registers andspregisters according to the contents saved in the B task context. Only after this step is done can__switchexecute a function across two control streams, i.e., the control stream is switched by changing the stack. - Phase [4]: After the previous step of register restoration, you can see that the sp register is restored and switched to the kernel stack of task B, thus enabling control flow switching. This is why

__switchis able to execute one function across two control streams. After that, when the CPU executes theretinstruction and the__switchfunction returns, task B can continue down the stack from where it called__switch.

As a result, we see that the states of control flow A and control flow B are swapped, with A entering a suspended state after saving the task context, while B resumes context and continues execution on the CPU.

# os/src/task/switch.S

.altmacro

.macro SAVE_SN n

sd s\n, (\n+2)*8(a0)

.endm

.macro LOAD_SN n

ld s\n, (\n+2)*8(a1)

.endm

.section .text

.globl __switch

__switch:

# Phase [1]

# __switch(

# current_task_cx_ptr: *mut TaskContext,

# next_task_cx_ptr: *const TaskContext

# )

# Phase [2]

# save kernel stack of current task

sd sp, 8(a0)

# save ra & s0~s11 of current execution

sd ra, 0(a0)

.set n, 0

.rept 12

SAVE_SN %n

.set n, n + 1

.endr

# Phase [3]

# restore ra & s0~s11 of next execution

ld ra, 0(a1)

.set n, 0

.rept 12

LOAD_SN %n

.set n, n + 1

.endr

# restore kernel stack of next task

ld sp, 8(a1)

# Phase [4]

ret

It is important to save ra, which records where to jump to after the __switch function returns so that you can get to the correct location after the task switch is complete and ret. For normal functions, the Rust/C compiler automatically generates code at the beginning of the function to save the registers s0 to s11 that are saved by the caller. However, __switch is a special function written in assembly code that is not processed by the Rust/C compiler, so we need to manually write assembly code in __switch to save s0~s11. There is no need to save other registers because: among the other registers, those belonging to the caller’s save are done by the code automatically generated by the compiler in the call function written in high-level language; and some registers belong to temporary registers, which do not need to be saved and restored.

We will interpret the global symbol __switch in this assembly code as a Rust function:

// os/src/task/context.rs

pub struct TaskContext {

ra: usize,

sp: usize,

s: [usize; 12],

}

// os/src/task/switch.rs

global_asm!(include_str!("switch.S"));

use super::TaskContext;

extern "C" {

pub fn __switch(

current_task_cx_ptr: *mut TaskContext,

next_task_cx_ptr: *const TaskContext

);

}

We will call this function to complete the switch function instead of jumping directly to the address of the symbol __switch. So the Rust compiler will automatically help us insert assembly code that saves/restores the caller’s save register before and after the call.

0x02 Task Scheduling

Preemptive Scheduling

Modern task scheduling algorithms are basically preemptive in nature, requiring that each application can only execute continuously for a certain period of time before the kernel forces it to switch out. A Time Slice is generally used as a unit of measure for the length of continuous execution of an application, and each time slice may be in the order of milliseconds. The scheduling algorithm needs to consider how many time slices an application is given to execute before switching out, and which application to switch into. The scheduling algorithm can be evaluated in terms of performance (mainly throughput and latency metrics) and fairness, which requires that the percentage of time slices allocated to multiple applications should not vary too much.

The core mechanism of scheduling lies in timing: we use clock interrupts to forcibly block the execution of user-state programs, thus allowing the OS to use the CPU and exercise its task management powers.

// os/src/trap/mod.rs

match scause.cause() {

Trap::Interrupt(Interrupt::SupervisorTimer) => {

set_next_trigger();

suspend_current_and_run_next();

}

}

// os/src/main.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub fn rust_main() -> ! {

clear_bss();

println!("[kernel] Hello, world!");

trap::init();

loader::load_apps();

trap::enable_timer_interrupt();

timer::set_next_trigger();

task::run_first_task();

panic!("Unreachable in rust_main!");

}

// os/src/trap/mod.rs

use riscv::register::sie;

pub fn enable_timer_interrupt() {

unsafe { sie::set_stimer(); }

}

After an application has run for 10ms, an S privilege clock interrupt is triggered. Since the application is running at the U privilege and the sie register is set correctly, the interrupt is not masked, but jumps to our trap_handler inside the S privilege for processing and switches to the next application smoothly. This is the preemptive scheduling mechanism we expect.

Task Management

We use a global task manager to control all the scheduling:

mod context;

mod switch;

mod task;

pub mod scheduler;

use crate::config::MAX_APP_NUM;

use crate::loader::{get_num_app, init_app_cx};

use crate::sync::UPSafeCell;

use alloc::boxed::Box;

use lazy_static::*;

use switch::__switch;

use task::{TaskControlBlock, TaskStatus};

use scheduler::{BIG_STRIDE, StrideScheduler};

pub use context::TaskContext;

pub struct TaskManager {

num_app: usize,

inner: UPSafeCell<TaskManagerInner>,

}

struct TaskManagerInner {

tasks: [TaskControlBlock; MAX_APP_NUM],

current_task: usize,

scheduler: Box<StrideScheduler>,

}

lazy_static! {

pub static ref TASK_MANAGER: TaskManager = {

let num_app = get_num_app();

let mut stride_scheduler: StrideScheduler = StrideScheduler::new();

let mut tasks = [

TaskControlBlock {

id: 0,

task_cx: TaskContext::zero_init(),

task_status: TaskStatus::UnInit,

priority: 16,

pass: 0,

};

MAX_APP_NUM

];

for i in 0..num_app {

tasks[i].id = i;

tasks[i].task_cx = TaskContext::goto_restore(init_app_cx(i));

tasks[i].task_status = TaskStatus::Ready;

stride_scheduler.create_task(i);

}

TaskManager {

num_app,

inner: unsafe { UPSafeCell::new(TaskManagerInner {

tasks,

current_task: 0,

scheduler: Box::new(stride_scheduler),

})},

}

};

}

impl TaskManager {

fn run_first_task(&self) -> ! {

let mut inner = self.inner.exclusive_access();

let next = inner.scheduler.find_next_task().unwrap();// let it panic or not

let task0 = &mut inner.tasks[next];

task0.task_status = TaskStatus::Running;

let next_task_cx_ptr = &task0.task_cx as *const TaskContext;

drop(inner);

let mut _unused = TaskContext::zero_init();

// before this, we should drop local variables that must be dropped manually

unsafe {

__switch(

&mut _unused as *mut TaskContext,

next_task_cx_ptr,

);

}

panic!("unreachable in run_first_task!");

}

fn mark_current_suspended(&self) {

let mut inner = self.inner.exclusive_access();

let current = inner.current_task;

inner.tasks[current].task_status = TaskStatus::Ready;

}

fn mark_current_exited(&self) {

let mut inner = self.inner.exclusive_access();

let current = inner.current_task;

inner.tasks[current].task_status = TaskStatus::Exited;

}

fn find_next_task(&self) -> Option<usize> {

let mut inner = self.inner.exclusive_access();

loop {

let next = inner.scheduler.find_next_task();

if let Some(id) = next {

if inner.tasks[id].task_status == TaskStatus::Ready {

return next;

}else {

continue; // no ready so removed?

}

}else {

return None;

}

}

}

fn run_next_task(&self) {

let mut inner = self.inner.exclusive_access();

let current = inner.current_task;

inner.tasks[current].pass += BIG_STRIDE / inner.tasks[current].priority;

let current_pass = inner.tasks[current].pass;

inner.scheduler.insert_task(current, current_pass);

drop(inner);

if let Some(next) = self.find_next_task() {

let mut inner = self.inner.exclusive_access();

inner.tasks[next].task_status = TaskStatus::Running;

inner.current_task = next;

let current_task_cx_ptr = &mut inner.tasks[current].task_cx as *mut TaskContext;

let next_task_cx_ptr = &inner.tasks[next].task_cx as *const TaskContext;

drop(inner);

// before this, we should drop local variables that must be dropped manually

unsafe {

__switch(

current_task_cx_ptr,

next_task_cx_ptr,

);

}

// go back to user mode

} else {

panic!("All applications completed!");

}

}

fn set_current_prio(&self, prio: usize) {

let mut inner = self.inner.exclusive_access();

let current = inner.current_task;

inner.tasks[current].priority = prio;

}

}

pub fn run_first_task() {

TASK_MANAGER.run_first_task();

}

fn run_next_task() {

TASK_MANAGER.run_next_task();

}

fn mark_current_suspended() {

TASK_MANAGER.mark_current_suspended();

}

fn mark_current_exited() {

TASK_MANAGER.mark_current_exited();

}

pub fn set_current_prio(prio: usize) {

let prio = if prio < BIG_STRIDE {prio} else {BIG_STRIDE};

TASK_MANAGER.set_current_prio(prio);

}

pub fn suspend_current_and_run_next() {

mark_current_suspended();

run_next_task();

}

pub fn exit_current_and_run_next() {

mark_current_exited();

run_next_task();

}

Besides, we implemetend a stride scheduler(see Refrence 2), which enables priorities in scheduling:

use core::cmp::{Ord, Ordering};

use alloc::collections::BinaryHeap;

pub const BIG_STRIDE: usize = 1_000;

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Eq)]

pub struct Stride {

id: usize,

pass: usize,

}

impl Stride {

pub fn new(id: usize, pass: usize) -> Self {

Self { id, pass, }

}

pub fn zeros() -> Self {

Self { id: 0, pass: 0, }

}

}

impl Ord for Stride {

fn cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> Ordering {

self.pass.cmp(&other.pass).reverse()

}

}

impl PartialOrd for Stride {

fn partial_cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> Option<Ordering> {

Some(self.cmp(other))

}

}

impl PartialEq for Stride {

fn eq(&self, other: &Self) -> bool {

self.pass == other.pass

}

}

pub struct StrideScheduler {

queue: BinaryHeap<Stride>,

}

impl StrideScheduler {

pub fn new() -> Self {

Self {queue: BinaryHeap::new()}

}

pub fn create_task(&mut self, id: usize) {

self.queue.push(Stride::new(id, 0));

}

pub fn insert_task(&mut self, id: usize, pass: usize){

self.queue.push(Stride::new(id, pass));

}

pub fn find_next_task(&mut self) -> Option<usize> {

let next = self.queue.pop();

if let Some(node) = next {

Some(node.id)

} else {

None

}

}

}

Note that in order to use alloc::collections::BinaryHeap, we have to implement the global allocator, which will be illustrated in next chapter, see the mm submodule for details.

We use the code provided by rCore-Tutorial-Book-v3 to test the stride scheduler:

(base) test@HPserver:/home/test/rCore-dev/os$ make clean && make run TEST=3

(rustup target list | grep "riscv64gc-unknown-none-elf (installed)") || rustup target add riscv64gc-unknown-none-elf

riscv64gc-unknown-none-elf (installed)

cargo install cargo-binutils --vers =0.3.3

Ignored package `cargo-binutils v0.3.3` is already installed, use --force to override

rustup component add rust-src

info: component 'rust-src' is up to date

rustup component add llvm-tools-preview

info: component 'llvm-tools-preview' for target 'x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu' is up to date

make[1]: Entering directory '/home/qsp/rCore-dev/user'

Compiling scopeguard v1.1.0

Compiling spin v0.7.1

Compiling spin v0.5.2

Compiling bitflags v1.3.2

Compiling lock_api v0.4.6

Compiling lazy_static v1.4.0

Compiling buddy_system_allocator v0.6.0

Compiling spin v0.9.2

Compiling user_lib v0.1.0 (/home/qsp/rCore-dev/user)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 2.29s

[build.py] application test3_stride0 start with address 0x80400000

Compiling user_lib v0.1.0 (/home/qsp/rCore-dev/user)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.27s

[build.py] application test3_stride1 start with address 0x80420000

Compiling user_lib v0.1.0 (/home/qsp/rCore-dev/user)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.26s

[build.py] application test3_stride2 start with address 0x80440000

Compiling user_lib v0.1.0 (/home/qsp/rCore-dev/user)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.27s

[build.py] application test3_stride3 start with address 0x80460000

Compiling user_lib v0.1.0 (/home/qsp/rCore-dev/user)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.26s

[build.py] application test3_stride4 start with address 0x80480000

Compiling user_lib v0.1.0 (/home/qsp/rCore-dev/user)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.25s

[build.py] application test3_stride5 start with address 0x804a0000

make[1]: Leaving directory '/home/qsp/rCore-dev/user'

Platform: qemu

Compiling memchr v2.4.1

Compiling semver-parser v0.7.0

Compiling regex-syntax v0.6.25

Compiling lazy_static v1.4.0

Compiling log v0.4.14

Compiling cfg-if v1.0.0

Compiling bitflags v1.3.2

Compiling bit_field v0.10.1

Compiling spin v0.7.1

Compiling spin v0.5.2

Compiling os v0.1.0 (/home/qsp/rCore-dev/os)

Compiling buddy_system_allocator v0.6.0

Compiling semver v0.9.0

Compiling rustc_version v0.2.3

Compiling bare-metal v0.2.5

Compiling aho-corasick v0.7.18

Compiling regex v1.5.4

Compiling riscv-target v0.1.2

Compiling riscv v0.6.0 (https://github.com/rcore-os/riscv#11d43cf7)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 6.54s

[rustsbi] RustSBI version 0.2.0-alpha.6

.______ __ __ _______.___________. _______..______ __

| _ \ | | | | / | | / || _ \ | |

| |_) | | | | | | (----`---| |----`| (----`| |_) || |

| / | | | | \ \ | | \ \ | _ < | |

| |\ \----.| `--' |.----) | | | .----) | | |_) || |

| _| `._____| \______/ |_______/ |__| |_______/ |______/ |__|

[rustsbi] Implementation: RustSBI-QEMU Version 0.0.2

[rustsbi-dtb] Hart count: cluster0 with 1 cores

[rustsbi] misa: RV64ACDFIMSU

[rustsbi] mideleg: ssoft, stimer, sext (0x222)

[rustsbi] medeleg: ima, ia, bkpt, la, sa, uecall, ipage, lpage, spage (0xb1ab)

[rustsbi] pmp0: 0x10000000 ..= 0x10001fff (rwx)

[rustsbi] pmp1: 0x80000000 ..= 0x8fffffff (rwx)

[rustsbi] pmp2: 0x0 ..= 0xffffffffffffff (---)

qemu-system-riscv64: clint: invalid write: 00000004

[rustsbi] enter supervisor 0x80200000

[kernel] Hello, world!

priority = 9, exitcode = 35427600

priority = 10, exitcode = 39471200

priority = 8, exitcode = 31496000

[kernel] Application exited with code 0

[kernel] Application exited with code 0

priority = 7, exitcode = 27814000

priority = 6, exitcode = 23706000

[kernel] Application exited with code 0

[kernel] Application exited with code 0

priority = 5, exitcode = 19708000

[kernel] Application exited with code 0

[kernel] Application exited with code 0

Panicked at src/task/mod.rs:129 All applications completed!

The results are consistent with our prediction, with the running time of each program proportional to the priority.

0x03 References

- https://rcore-os.github.io/rCore-Tutorial-Book-v3/chapter3/

- https://nankai.gitbook.io/ucore-os-on-risc-v64/lab6/tiao-du-suan-fa-kuang-jia#stride-suan-fa

- https://web.eecs.utk.edu/~smarz1/courses/ece356/notes/assembly/

All of the figures credit to rCore-Tutorial-Book-v3